Streak cameras are used by chemists to capture light passing through samples and determine chemical properties. At the MIT Media Lab in Cambridge, Massachusetts, scientists have found a way to modify these streak cameras to capture motion – recording ultrashort pulses of light at up to a trillion frames per second. Project Director Dr. Ramesh Raskar calls this new technique “femto-photography.”

As described in the project abstract:

We have built an imaging solution that allows us to visualize propagation of light. The effective exposure time of each frame is two trillionths of a second and the resultant visualization depicts the movement of light at roughly half a trillion frames per second. Direct recording of reflected or scattered light at such a frame rate with sufficient brightness is nearly impossible. We use an indirect 'stroboscopic' method that records millions of repeated measurements by careful scanning in time and viewpoints. Then we rearrange the data to create a 'movie' of a nanosecond long event.

Femto-photography gained global recognition in June 2012, with Ramesh Raskar’s TED talk (full video below), which has received more than three million views to date. The prospect of using light scattering to analyze the stability of materials and gain more comprehensive medical images excites both academia and the industry alike.

When Dr. Raskar and Andreas Velten, then a postdoctoral researcher, set out to conduct research in this field, they didn’t initially have materials and medicine in mind. According to Raskar, “I was obsessed with doing computational photography with ultrafast imaging — to look around corners, relighting scenes after the fact and recovering 3D structure in presence of scattering.”

Velten saw femto-photography as an opportunity to work on a project with a computational focus where he could also use his optical engineering skills. “In a field like imaging, the separation between hardware and software does not make sense,” he said.

The technology has come a long way since it’s unveiling; numerous improvements have been made, including — as noted by the researchers — great progress with smaller, very low cost and potentially consumer grade hardware, and the development of consumer-ready time of flight cameras.

“The technology itself is ready, and can be applied in simple situations, such as characterizing bulk scattering samples,” said Raskar. He expects a wider range of applicability in the near future with further improvements to the system.

Velten, now affiliated with the Medical Devices Group at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, is currently working on applying femto-photography to the medical imaging applications hinted at in Ramesh’s TED talk. Though Velten is aware of the challenges present in using light scattering for accurate imaging, such as tracking the numerous bounces of light particles and observing much smaller time frames, he is optimistic. “The large scope of the biomedical potential will be unlocked gradually, application by application, by several research groups,” he said.

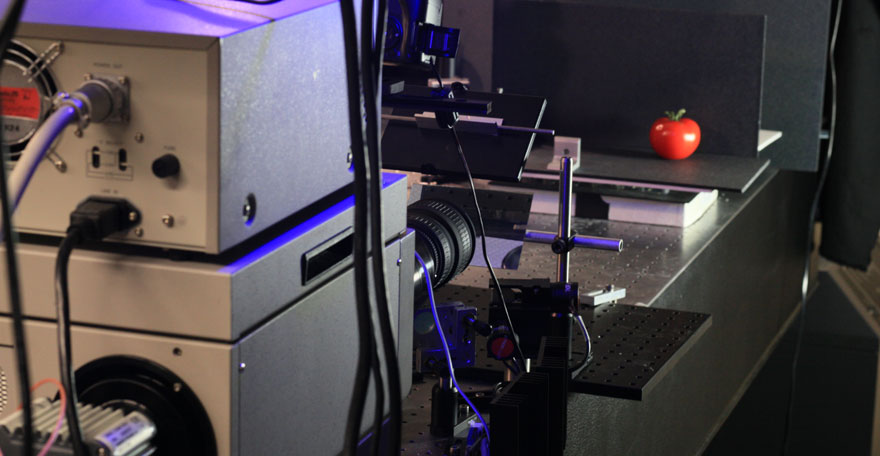

One of the most noticeable differences between a femto-photographic camera and any other camera is the dimensions of the device. Although large and heavy, neither Raskar nor Velten see an issue with portability. According to Velten, the camera is still portable enough for many uses; it could even be mounted on a fire truck and used to scan burning buildings for trapped victims.

The ongoing research and development into femto-photographic applications and improvements highlights the massive impact this technology could have in the years to come. Already capable of supporting numerous commercial applications, it is perhaps only a matter of time before femto-photography moves from cutting-edge research to commonplace imaging technology.

For more information on femto-photography, visit the MIT Media Lab femto-photography project website or download the ACM Transactions on Graphics article Femto-photography: capturing and visualizing the propagation of light.