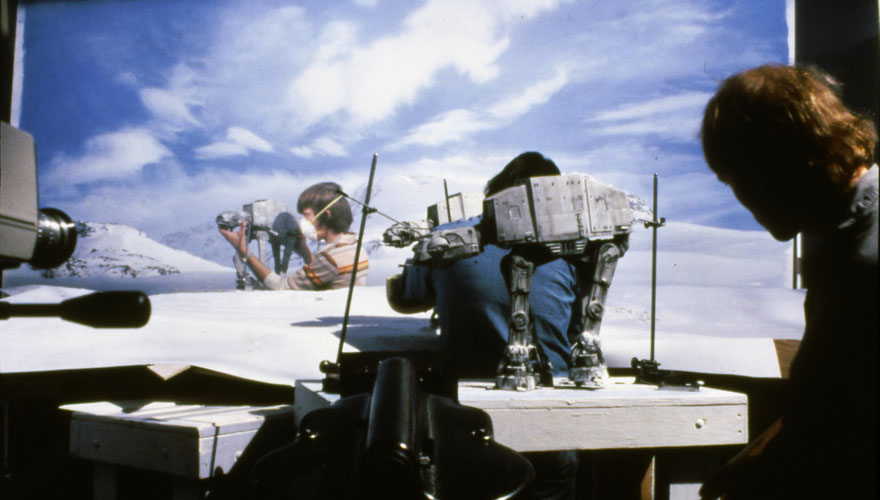

Up until the mid ‘90s, effects artists were people who made things with their hands. They wore paint-spattered clothing and rifled through tool boxes. They created aliens out of latex, turned foam into granite and constructed nine-foot spaceships from odds and ends found on dusty workshop shelves. The Millennium Falcon was a product of such physical craftsmanship, as was the creepy-yet-loveable E.T., the immaculate Discovery spacecraft in "2001: A Space Odyssey" and Major Toht’s grisly melting head in "Raiders of the Lost Ark."

Today, people with the knowledge and skill to create such models and effects are surprisingly rare. The vast majority of modern visual effects are created on computers, and artists-in-training learn software, not soldering. Computer graphics (CG) technology has advanced to the point where models and effects can now be rendered with near-perfect photorealism, and countless directors have stopped using physical effects altogether. Though the science and artistry involved in the creation of movie-quality computer graphics is tremendous, should that necessarily mean the complete extinction of practical effects — a field that only hit its stride a few decades ago?

When computer graphics first came on the scene in the early '80s, the technology was a novelty. It was a party trick to admire and wonder at, but nothing that came close to the realism of physical models Visual effects artist Lorne Peterson ("Star Wars" episodes I, II, III, IV, V and VI, "Jurassic Park," "Raiders of the Lost Ark," "E.T.") distinctly remembers the moment when computer graphics entered his world. It was the early ‘80s and Peterson was sitting at his desk at Industrial Light & Magic, working on a model for an upcoming film. Visual effects supervisor Dennis Muren popped his head in the door and waved to Peterson from across the room. “You’ve got to see this!” he said.

Peterson followed Muren to another part of the facility, where a fellow ILM employee was sitting before a 12-inch, state-of-the-art Macintosh computer. Peterson recalls peering over the man’s shoulder to see what he was working on. It was a shot from "Star Wars: Episode VI," which ILM had just finished, with a computer-generated shadow rendered over top of it. The shadow cascaded across the Death Star with surprising realism. Peterson was impressed, but far from dazzled by the new technology. “I thought…wow, that’s pretty neat. That will be handy for shadows…but probably not much else.”

Peterson is not the only one who was taken by surprise by the rapid adoption of computer graphics. Model maker Fon Davis has worked in the industry for more than two decades, and created models for all three of the Star Wars prequels. According to Fon, both computer graphics and practical effects have their place, but physical models possess certain inimitable qualities. “There is a randomness that occurs with a real object’s texture, aging and shadows,” he said. “A lot of people can spot CG even though they can’t put their finger on why. It’s really hard to fool the human brain.”

Scott Squires, an Academy Award-nominated visual effects supervisor and 35-year industry veteran, is a big fan of computer graphics — but admits that digital has its downsides. “One of the problems with computer-generated models is that they’re perfect. An example is mirror windows on a skyscraper. By default, a CG version represents each window as perfectly flat and aligned. But in reality, skyscraper windows are not perfectly flat — nor are they aligned. This takes both time and effort in CG to consider and to accomplish.”

Imperfect as they may be, digital effects have come a long way since "Tron." Modern computer graphics are highly sophisticated, and afford directors a greater degree of flexibility than practical effects. With digital effects, there are no restrictions on how many times a director can change his mind (aside from time and budget), and no production constrains (such as having a single take to blow up a $2 million model).

Scott Ross, who served as the general manager of ILM in the ‘80s and co-founded the post-production studio Digital Domain, explains. “There are limitations to physical models,” he said. “But CG can do just about anything… set extensions, fire, water, snow, pyro, creature animation, matte paintings — virtually anything you can imagine. In fact, nowadays, anything you can imagine.”

A few years back, director Peter Jackson made the decision to digitally re-imagine some of the creatures of Middle-earth for "The Hobbit" trilogy. The same creatures (orcs and goblins) appeared in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, but as actors in foam latex prosthetics, courtesy of Weta Workshop. In a November 2012 interview with the LA Times, Jackson explained that he decided to switch to computer graphics so he could make the beasts appear less human. “Prosthetic makeup is always frustrating,” he said. “At the end of the day, if you want the character to talk, which a lot of the orcs and goblins do, you can design the most incredible prosthetics — but you’ve still got eyes where the eyes have to be and the mouth where the mouth has to be.” The resulting computer-generated orcs and goblins were skillfully crafted, but to some fans, lacked the grit and realism of their prosthetic-clad predecessors.

Many industry veterans believe the best approach to creating realistic environments and creatures is to use a combination of physical and digital effects, selecting the approach that works best for each shot. Model maker Fon Davis is one such veteran. “I’ve learned from people like Dennis Muren that it really helps your CG artists if you shoot something practical to be used as reference,” he said. “Then, there’s no question what a real object looks like on camera in that environment and lighting.”

Unfortunately, not everyone making the decisions in Hollywood feels the same way. According to Scott Squires, “Model making is becoming a lost art of sorts. Many of the new visual effects companies do not have practical model shops.”

In fact, physical model making is a skill that’s rarely taught these days. Ben Fox, an FX technical director at Framestore, NY, grew up with a love for the traditional arts and hands-on creating. If he’d been born 20 years earlier, he might have been drawn to model making. As it was, practical effects work wasn’t even on his radar. “I never had the opportunity to take any model or miniature-making courses in college,” he said. “Though, come to think of it, that would have been great.”

While the demand for physical models may be waning, the appreciation for them is not. When Lorne Peterson and the rest of the ILM model shop got a chance to revisit the Star Wars universe in 1998 (creating models for the prequels), he was surprised to find the workshop regularly besieged by visitors from the computer graphics department. “They were mostly young guys,” Peterson said. “Star Wars was what made them fall in love with visual effects in the first place.” The CG staff visited so frequently to watch the model makers work that ILM had to institute a sign-up policy to limit the number of visitors in the workshop at any given time.

Though practical effects may have become eclipsed by computer graphics, they haven’t gone the way of the dinosaur just yet. In an August 2014 interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Rian Johnson (the future director of "Star Wars: Episode VIII") complained about the lack of practical effects in modern movies – and pointed out that "Star Wars: Episode VII" will be different from the Star Wars prequels in that respect. “They’re doing so much practical building for this one,” Johnson said. “It’s awesome.”

The question remains: do films like "Star Wars: Episode VII" represent the last gasp of practical effects? Or could Episode VII's release mark the beginning of a new era: one where practical and digital effects are not in competition, but acknowledged as equally important parts of the filmmaking toolset, used together to create the most realistic environments, characters and effects possible?

When asked what he thought the future might hold for model makers and other practical effects artists, Lorne Peterson laughed, recalling his first introduction to computer graphics. “I’m terrible at predicting the future,” he said. “Don’t ask me.”